Making the Paintings

Two Eleven

Left to rt: having built a 56-room cabinet only three full slots end up visible in the painting; artist in residence - Rue de la Calade, Arles; baju (c.1950) by Yeong Seng, tailor in the Penang Road, original and remade hotel key fobs; constructing the key cabinet.

Beauty Coming Down

Macalister Road, 1415 & Subtitle

How do you go about making a painting?

Having conceived an idea for a picture I will go about setting up a shoot, giving consideration to casting, location, props, lighting / time of day. Hoping to get that one image I'll take several rolls of film using a SLR camera.

The photographs come back from the lab normal postcard size. One is selected, scanned and blown up to 60 x 40 cm. I trace and then transfer an outline guide to the paper. Reverting to the original postcard size photo as my 'model', everything is re drawn with water soluble colour pencil. I switch to brush and with watercolour slowly build up the image layer upon layer, the pencil outlines get washed away.

Photography therefore plays a major part in this process.

I think the main reason to choose the camera as my viewfinder on the world is that it has an entirely objective way of recording reality. In several other aspects too the camera can capture what the eye cannot. Composition with the crop of the viewfinder; distance (focal planes) with apperture settings; time, the speed of the shutter can hold a split second.

On a more practical level, these paintings take a long time to do (well over a year what with one thing and another for Zabriskie Point), it helps that your life model can keep still for this length of time.

You are simply copying a photograph?

I do stick as closely as possible to the photograph because it embodies the objective reality I want to show. It stands for itself. There is no need for the artist to intrude or interpret, much less to be seen to have been at work with signature brushwork whatever. One has only to consider that if those original moments of beauty, space, existence are from god then the look-at-me stuff doesn't really come into it.

I prefer that there is as little evidence of how the painting has arrived on the paper as possible, it appears entirely of itself.

Ars est celare artem?

Yes, art is to conceal art.

Why not just leave it as a photograph?

The photos I take are actually rather poor quality, as soon as they are enlarged at all they get progressively fuzzier - it's like looking at something without your specs on. Part of the process of the painting is to adjust the blurr to give the right amount of definition. Besides there can be something quite miraculous about a painting, photographs have quite different qualities.

Why do you use watercolour?

I love the way in which you are always working with the whiteness of the paper, this is what illuminates the image. You never add white to make a colour or tone, untouched paper is the highlight, thence by degrees of transparency and hue to the darkest shade - similar to the way images appear on the cinema screen. This is also perhaps why I prefer to use black to matt the image, it gives a sense of light coming from within the picture as if you are sitting in a darkened cinema watching a movie.

Where do you draw inspiration for your work?

I think mostly from those works by artists imbued with a sense of the temporal. This would include individual works like Norman Rockwell's Shuffleton's Barbershop, the watercolours of Andrew Wyeth, of course Vermeer.

Time to time I return to particular films of Antonioni and Ozu, also those of Vietnamese director Tran Anh Hung.

Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven captures so much purely by visual means.

I have a strong recollection of the Hayward show of the Boyle Family's landscapes.

Recently I listened to an audio version of Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard read by Corin Redgrave.

Strauss's Four Last Songs.

The list would be quite long.

You mention the temporal, but you have done religious paintings as well?

That's true, possibly the temporal and the spirtual are two sides of the same coin.

Aubert Park, London. December 2007

Nicholas Phillips: Inspiration and Respite

ARTIST INTERVIEW Published: 30th October 2024 by Josephine Zentner

Nicholas Phillips won the Watercolour Award in the Jackson’s Art Prize this year with his work Boundary Line. In this interview, Nicholas shares a detailed account of his meticulous watercolour painting process, along with the work-in-progress images of his award-winning artwork.

Above image: Nicholas Phillips in his studio.

Boundary Line, 2023

Nicholas Phillips

Watercolour on paper, 26 x 40 cm

Josephine: Could you tell us about your artistic background?

Nicholas: After graduating from art school in 1978, I spent 10 years endeavouring to find a place in the world of fine art. In 1988, going nowhere, I decided to quit art completely and started a commercial decorating business. After 10 years or so, the calling came back and I started painting pictures again in between contracts on building sites here and abroad. I have since carried on more or less continuously, ceasing commercial work in 2012. In these last 24 years, I have totalled 40 pictures.

Studio view: Fully south facing – a job to control the daylight!

Josephine: What does a typical working day in the studio look like for you? Do you have any important routines or rituals?

Nicholas: Now I’m a state pensioner I have the great good fortune to work at will – roughly a five-hour day at the table, five days a week.

Josephine: Which materials or tools could you not live without?

Nicholas: That would be the camera. For session work: a rather old 90s Canon EOS Kiss with various lenses. My day-to-day is an iPhone SE.

Penang Turf Club, 2013

Nicholas Phillips

Watercolour, 70 x 45 cm

Josephine: What are the stages of your work on a painting/drawing/? Do you make drafts?

Nicholas:

1. Landing the image: the photograph. This is the core creative part of my picture-making process. Achieving this can take more than one session: three visits to the location for Boundary Line, and many hundreds of shots for The Villa Salina. Then sometimes, as in the case of Crossing at Kitakamakura, it’ll be just that one chance shot that jumps right out at you as what it is you want to convey. In the past, for the larger paintings, I would build a set for the photo shoot and assemble props and costumes – see Penang Turf Club, all in the living room of our flat in Highbury, London!

2. Prep work. Size the photo in Photoshop. Mostly I like to make no adjustments to the chosen image – it is about retaining that vital moment the shutter clicked. Paper and support: I use Arches 300 gsm hot pressed paper stretched (permanently) to Klug Conservation honeycomb board.

3. Trace and transfer. From a digital printout of the image, I make a tracing with the help of the Daylight A3 lightbox. Back with Caran d’Ache Supracolour Soft pencil. Trace guidelines onto the Arches.

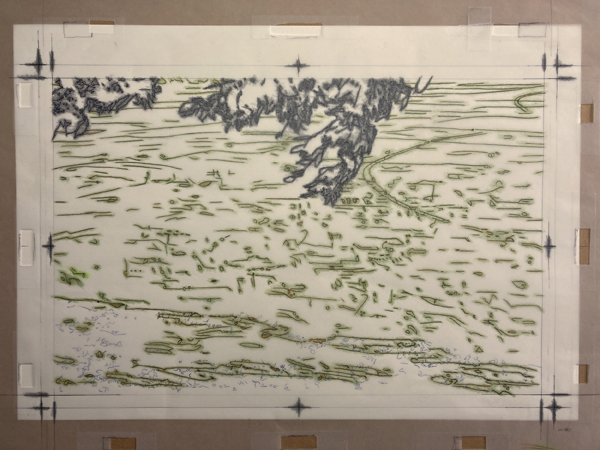

Boundary Line Work in progress week 2 / 22

Tracing ready to be drawn through to the Arches

4. Map out the composition. Building up with the watercolour the Caran d’Ache under-drawing will dissolve and disappear. The yellow is the tinting in the Winsor & Newton Masking Fluid.

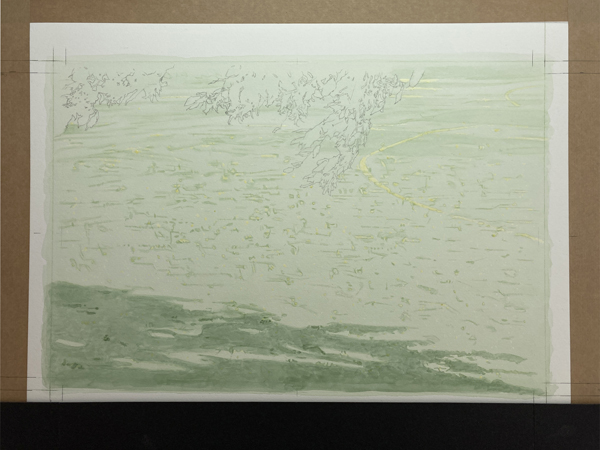

Boundary Line Work in progress week 6 / 22

Beginning to replace the Caran d’Ache pencil drawing with watercolour.

5. Continue. I can never, ever, get things right the first go. I have great admiration for painters who can. See the dazzling Cuban watercolours of Rance Jones – the sheer sure-footedness of his brushwork, the freshness of colour, the light, the life! It is, therefore, months of slowly, mechanically, building up what’s where: tuning hue, arriving at the tonal balances, by using a combination of washes, dry brush for blends, repeat masking (grass requires gallons of the stuff), spotting (the Arches doesn’t take the colour evenly after successive workings).

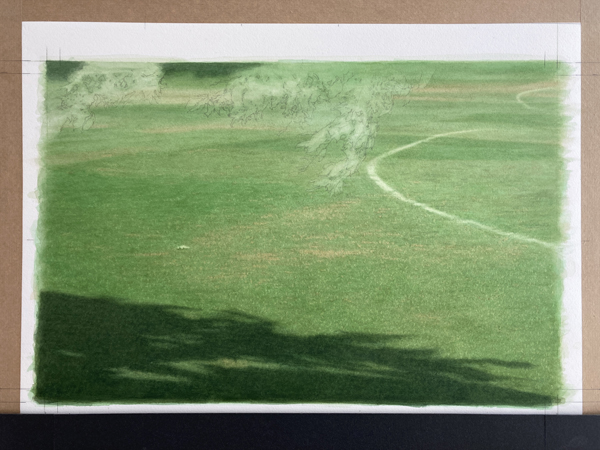

Boundary Line Work in progress week 14 / 22

Building up the image with successive washes, maskings.

I like the idea that the image has appeared of itself, something seamless, without trace of human hand/brushmark. The image is of its own importance, not a proclamation of some signature artist.

Incidentally, to answer the question, why bother to so literally reproduce a photo? Of course on screen the reproduction will look like a photo so it’s only when you see the actual piece – see the surface, the paper, the pigmentation, that you may, hopefully, appreciate what a marvel a painting in watercolour is. Photographs are also wonderful things but are really of a different order.

6. My work table/painting cabinet. The cut-down water bottle must be over 20 years in use. Porcelain palettes. Distilled water. Winsor & Newton watercolour tubes, although I’m now switching to their pans which fit handily into Muji’s Pill Cases – this helps minimise dust collecting in the paint. Brushes: the two black-handled sables are very old and out of shape – they’re for general mixing and ideal for dry brush. The white 10/0 Pro Arte is great for spotting – keeps point very well. Indeed looking at my brush drawer the majority of the finer brushes are Pro Arte synthetic watercolour brushes.

Studio view: Work table and painting cabinet.

Josephine: Do you regularly draw or keep a sketchbook? If so, how does this inform your work?

Nicholas: Source material comes via the camera.

Josephine: Have you ever had a period of stagnation in creativity? If so, what helped you overcome it?

Nicholas: One advantage to working so slowly – one or two paintings a year, and then in a totally mechanical way, is that stagnation is kind of built-in. I only need to be creative once or twice a year.

Crossing at Kitakamakura, 2018-21

Nicholas Phillips

Watercolour, 40 x 27 cm

Josephine: Are there any specific artists or mentors who have inspired you?

Nicholas: Books, films, pictures, and music. There are so many wonderful artists and works that are a constant inspiration and respite. Recently: Wim Wenders' film Perfect Days; I never knew about Saul Leiter’s work until the show at Milton Keynes Gallery this last Spring. Perennially? that would be quite a list, Giuseppe di Lampedusa would probably be at the top.

Josephine: How did it feel to realise you had won the Watercolour Award?

Nicholas: Surprised, very pleasantly surprised. It has been my experience that paintings assiduously copied from photos rarely register. That said, Vessel was long-listed in Jackson’s Painting Prize a few years ago. Hats off to Jackson’s for providing this platform.

The Villa Salina, 2016-17

Nicholas Phillips

Watercolour, 40 x 26 cm

Josephine: How long does a painting like Boundary Line take to complete?

Nicholas: Boundary Line took about five months.

Josephine: How do you take care of your brushes to enable you to use them in such a controlled way?

Nicholas: The finer brushes do have a working life and need periodically to be replaced. The older sables keep going and get better as they lose their point. I don’t often use soap as I read somewhere it can affect the paper’s sizing. However, before using masking fluid I wash the brush, squeeze it out but leave a light coating of the soap – this makes it easier to clean away the coagulated latex.

Boundary Line Work in progress week 19 / 22

Studio view of watercolour nearly finished within antique frame.

Josephine: What’s coming up next for you?

Nicholas: A painting of a puddle near here. It is on a track through the water meadows just across the river. A scene that, in my imagination, could feature a number of floating bodhisattvas.